That I was born in Havana in 1960, “in the fist of the Revolution” to use the phraseology of the island Cubans (this “island Cuban” versus “Miami Cuban” business can lead to schizophrenia, unless one is agile at linguistic somersaults), had a decisive impact on my decision to revert to Islam in the summer of 2000. Fidel Castro has often said that a revolution allows no neutrals. From the moment a child reaches school-age in Cuba he or she is confronted with problems of war and peace, justice and oppression, and integration or marginalization from family, friends, neighbors, and nation.

Was I for or against the Revolution of 1959? Where did I belong – with my parents who were officially dubbed “gusanos” (counterrevolutionary worms) or with my mother’s side of the family, members of which belonged to the Communist Party? These were playground questions for me, not theoretical debates. The Revolution brought justice – I could see it in the improvement of the lives of my relatives – but also repression: the fear of speaking out that I registered whenever my parents conversed privately about politics.

My father made the decision to take our family out of Cuba in 1968. The experience was particularly traumatic for me, being an only child, since I was leaving behind my cousins, who all belonged to the Castroite side of the clan. Moving to Los Angeles where my father’s sister resided, my parents followed the usual Latin American Catholic practice when it come to religion: walk the walk, just don’t talk the talk. I was pushed into parochial school, and sent to Sunday mass on special occasions like Epiphany or the Day of the Three Kings (I still remember, back in Cuba, putting out hay for their horses in order to receive presents on January 6). At the same time, Catholicism was never mentioned at home – no prayer, invocation of God, or mention of Jesus (peace be upon him) for help and salvation.

Mercifully, the priests and nuns at the high school I attended during the 1970s deprogrammed me from Christianity. What can I possibly say about putative Christians who blessed the Vietnam War? After three years of this ridiculous situation, I screamed for a release and received my parents consent to transfer to a public high school. I also became an agnostic, a view I maintained until finding Islam.

My release from parochial school and enrollment at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) in 1980, majoring in history and specializing in Brazil, furthered my estrangement from organized religion. The 1980s posed terrible and challenging tasks for Latinos on campus. Our brothers and sisters in Central America were being butchered by American-trained death-squads daily. Poverty and unemployment inside the United States surged while the rich grew fatter under the presidency of Ronald Reagan.

I joined several organizations at UCLA dedicated to ending this horror. Politics became a substitute religion for me, not just a way to fight back against oppression but a substance to fill the void I had felt ever since childhood – the unfulfilled need to bring social justice to the world. But, as anyone who has ever dived into politics can attest, the terrible irony is that the deeper the commitment, the greater the alienation. Petty squabbles inside an organization turn into political purges, and close friends become demons once they deviate from the party line. Quickly, I turned into a cynic, and like many burnt-out politicos, took to drink.

1991: the USSR is gone, the Sandinistas in Nicaragua have been defeated at the polls, the Salvadoran rebels disarm, and Cuba enters the worst economic crisis in history, leaving my island relatives pleading with me and my mother to send anything and everything we can back home, even a bottle of aspirin. Personally, however, I had started to walk the long road back to recovery, alhamdulillah (all thanks be to Allah). That year I gave up drinking for good, received my doctorate in History from UCLA, and headed into the job market.

The next year, I married a sweet Korean-American woman of my age, and landed a tenure-track job at Kent State University (KSU) of Ohio, teaching the History of Latin America and the History of Civilization. After seven years of research, I turned my manuscript on the shantytowns of Rio de Janeiro into a book, Family and Favela, published in 1997. Professionally, I never felt more satisfied, but over the horizon loomed a crisis that nearly wrecked my life. I was mad at my parents for not giving me a happier childhood, estranged from my wife, and numbing myself again, this time not through alcohol but by buying entertainment appliances to fill up my empty heart.

In the same manner of other fools who score victories in their careers, I had begun to take my family for granted. Without going into the sordid details, I will say that my emotional blindness almost cost me my marriage. For six agonizing months, my wife left me, and not a day went by that I did not cry and scream like an animal for her to return. I got down on my knees and prayed to whatever higher power might exist to grant me the courage of Jesus, Buddha, and Muhammad just to survive.

The only thing I knew for sure about these messengers is that they underwent and understood personal tragedy and yet came out victorious, charged with a mission to help others in distress. The supplication (today I would say dua’) was answered. My wife came back, although I did not merit such mercy from Allah, and this miracle made me want to explore why the Divinity, which I was now sure existed, would want to help me.

Still, even the unorthodox Christianity preached by the mystics seemed unrewarding. Surrendering myself blindly to Christ, even if he was the Son of God, took me back to parochial school. It provided no detailed answers on how to restructure my life so that the outside me, the husband and successful professor, coincided with the inside-me – the insecure creature too frightened to taste life.

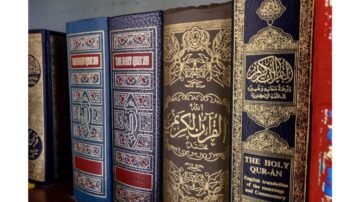

Sometime in the mid-90s, I purchased the famous Muhammad Pickthall translation of the meanings of the Holy Qur’an for the sake of augmenting my history lectures on Islam. I had never gotten around to reading it. Then, on a trip from Cleveland to Miami in 1999, for some reason I decided to take it along on the plane. I recall the woman in the seat next to me asking what I was reading. “The Qur’an,” I replied brusquely. She stared at me in perplexity. “The holy book of the Muslims,” I added for her benefit.

She asked, “Is that what you are?”

I replied, “No, I’m just interested in world literature.” I devoured roughly half the book during the plane ride of two hours and finished it during my stay at my parents’ house. What amazed me is that the book addressed everything – from usury to divorce to women’s rights. All religions claim they are more than just a religion but a complete way of life, but only in Islam is this vow fulfilled. Do Catholics arrange their day around prayer? I asked myself. Is Buddhism anything more than just playing with the meaning of words? I reflected on the lectures I gave in my History of Civilization course. What had I been teaching the students at Kent State about Islam? – That it was the most democratic and egalitarian of all the world’s religions since it recognized no distinction or merit based on race, social class, nationality or gender. Rather merit was based only on degrees of faith. But now, for the first time, the words hit home. All that was needed to make my conversion final was a triggering event.

Recife, Brazil: June, 2000. I was attending a conference of scholars who specialize in Brazil. For reading material I brought along a book of Sufi poetry and prayers, which I had perused during my “mystical” phase but had never finished. Up in my hotel room, between sessions of the conference, I finally reached the last page and tucked the book away in my luggage. Later, walking along the lovely beach, I flashed back to the book hidden inside my layers of clothes. A voice from inside says, “This is what I want to be, and will be from now onwards – a Muslim.”

After returning to the United States, I tried to find some local Muslims. But how? Should I just look up “Islam” in the telephone book? Suddenly, I remembered that I once had a student in my Latin America class, an African-American young man named Musa. He was a quiet but very resourceful and devoted brother who, when not attending KSU, worked with troubled teens in Akron. He had told me that there was a small mosque in Akron, and that I was welcome to visit any time.

The Internet found the address for me. Knowing that Jummah services were held on Friday, I spent Thursday night on my knees praying to Allah to do the best thing for me. Was I worthy of joining the Ummah (Islamic nation)? How would I be received, since there are relatively few Latino Muslims? As I prayed I felt tears flowing down my face, for the first time in many years. Something dramatic was about to happen in my life, I knew it.

That Friday, I drove from Kent to Akron to attend my first Jummah prayer. Walking upstairs of the modest two-tiered mosque, I was startled by the variety of faces: African-Americans, South Asians, one brother who “even looked European”, as I said silently to myself, and several Arabs, including the Imam. He gave a fiery but controlled khutba (sermon). I do not remember the topic, but will never forget his frequent incantation: “O, Slaves of Allah!” That phrase resonates for me until this day. Why would anyone want to be a “slave” of the Divinity? I found the answer surrounding me that day: men of resolution, at peace with themselves, because they had surrendered their lives to Allah to do with as He willed.

The following week I came back, and after the sermon, I shyly asked one of the brothers if he would be witness to my conversion. Much to my surprise, he called the entire congregation to gather around me. The Imam administered the Shahada (public declaration of faith), and what I remember most was his promise, “All your previous sins are forgiven. On the Day Of Judgment, we shall be your witnesses that you took the Shahada in front of us.” Julio Cèsar Pino died that day, and Assad Jibril Pino was born.

After the obligatory bath, my next step was to contact my parents. I knew no phone call could express my joy, nor encompass the teachings of Islam, a religion totally unknown to them. Thus, I wrote them a long letter, and included a Spanish translation of the Surah al-Fatiha (the opening chapter of the Qur’an). Almost three years later, I still think my parents “don’t really get it” – they can’t comprehend why and how Islam changed my life, but they are tolerant. I wish I could say the same for some of my colleagues at the university. Embracing Islam is one thing; practicing Islam and fulfilling its obligations is something else. When I wrote and spoke publicly concerning the genocide of the Palestinians in 2001, I was subject to defamation, harassment, and even death threats in my office. Nonetheless, that’s fairly standard fare for most Muslims in America.

Nothing comes before my faith now. What I love most about Islam is precisely the discipline it requires of the believers – so that we may be one community. I always thought of myself as a disciplined person, but it took Islam to make me realize I was disciplining myself over the wrong things. In my days before Islam, I would say, “I have to be at that movie theater exactly at seven. I have to be first in line.” Today, after performing my morning prayers, I ask myself what I can do to advance Islam, even in a small way. It might require phoning my congressman to obtain a visa for a foreign brother who wants to come to the U.S., or perhaps sending money to a mosque in Nigeria.

Professionally, I have undergone conversion also. My current research project involves the lives of Muslim slaves in 19th-century Brazil, and their continual connection to their African homelands. In my History of Civilization class, which made me interested in Islam in the first place, I now always include the contemporary Middle East, and have had the pleasure of hosting Palestinian guest speakers. Almost all of my students enjoy this part of the course, and some have even asked me to teach a class exclusively on the history of Islam.

In my period of jahiliyya (days before Islam), depending on how I felt that day, I would those who asked that I was Cuban, Cuban-American, or even American (if I happened to be living in Brazil). Now, I just say Muslim, and leave it up to them to place me in a category. If they are pleased, and curious, then by permission of Allah, I tell them the astonishing story of how a Cubano became a Muslim.

By Julio Cèsar Pino